This could be the start of something big.

Or maybe small. A small idea that brings you round again to an old place in your heart, maybe from a long time ago.

The possibilities are endless—what to take with you? What to leave behind? A plethora of first-world problems assail you. Is your passport expired?

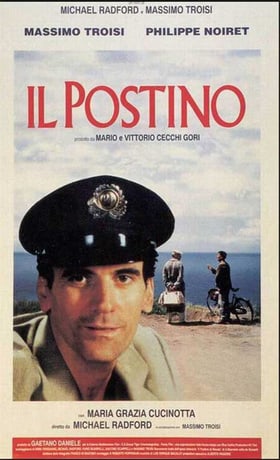

It all started with a lucky accident. Hungry for language (or maybe just something to focus on besides the red and blue political news channels) I set out to learn Italian. Which led me straight back to Il Postino, that glorious 1994 movie in which the postman delivers mail to just one client, the famous poet Pablo Neruda, (Phillippe Noiret) who is in exile from Chile and living in Italy.

But because I couldn’t get the subtitles to come up, and because my Italian wasn’t that good, I was watched it over and over. And thus was beguiled.

Everyone, it seems, watched the gorgeous movie long ago, but now the memory grows dim. I would like to resurrect it. Massimo Troisi, the director/star who died hours after filming ended, plays Mario, il Postino. Tongue-tied, he woos the fetching village barmaid, Beatrice (Dante’s love). He succeeds by stealing his new friend Pablo’s poetry to win her over, a la Cyrano de Bergerac.

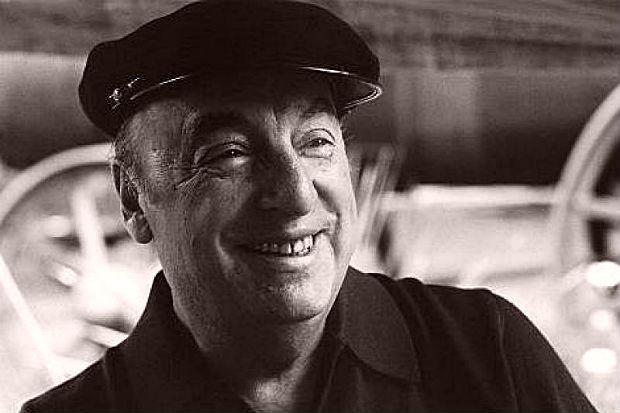

When someone asked me if I had family in Italy, I said, yes. But besides meeting up with my sister for six days, my secret “Italian” family is Pablo Neruda and Massimo Troisi. In my fantasy, I am privy to their unlikely and tender friendship. For a moment, I imagine a world in which there are no boatloads of desperate refugees off the coast of Sicily, no bad endings, no dangerous politics. No. We are in Procida, where much of the movie was filmed. We are back in time, and we meet along the sea.

Momentarily, we focus on life’s pleasure. We eat with gusto: filetto de sgombro in agrodolce, washed down with full-bodied vigna flaminia. Massimo’s delicate fingers curl around his glass. He looks up at us both with his dark eyes, pools of sensitivity.

They wonder: Why have I come? The waves hiss and sigh.

Ah, but I have come for just this moment.

I tell Senor Pablo how I know him. I tell him how 12 years ago I visited all of his three houses in Chile. I describe traveling the dizzying roads high in the Andes, high on Dramamine and his poetry, in Spanish in English. I tell him about the condors outside the bus windows, with 12-foot wingspans. I tell him his houses explain his longing for the sea, even though he was an armchair sailor. I know he has collected the world’s largest Narwhal tusk, (what’s that about, I refrain from asking) and ships in bottles. I explain how lovely it was, the carved, womanly ship’s prows, sailing bosom-first into the rooms. I tell him I secretly saw the suit he wore to receive the Nobel Prize, still tucked away in his closet.

“You should have had a Nobel prize for collecting,” I say, “though I like your poetry very much.”

He laughs. Have I offended? No; his passion for odd and lovely things mirrors my own. Objects are like writing: By moving things around, as if they were words, stories, paragraphs, we uncover surprising new narratives.

Mario is one of the few souls in a fishing village literate enough to deliver mail and to be changed by poetry. Also, he has a bicycle. Now Mario confesses: “I want to be a poet.” Senor Pablo argues, “It is more original to be a postman.”

But perhaps the deeper story turns on “metafore” a word that took me five viewings to translate into “metaphor.” Beatrice’s widowed aunt is furious because “any man who puts his words on you, the hands are not far behind.” “Metafore!” she spits out, like Hecate, as if it were dangerous, which of course it is. “Words are the worst thing ever,” she says. She may be right about that too.

Though Mario does not technically understand poetic concepts, his heart knows what it knows. When he hears the phrase: “I’m tired of being a man” Mario nods. “That happens to me too but I never knew how to say it.” Neither do I. I do not yet have words for what it is I seek.

“Better than any explanation is the expansion of feeling that poetry can reveal to a mind that is open enough to understand it,” says Neruda. But if you substitute the word “travel” for “poetry” you know what I mean.

The worldly Neruda pours me another glass of Rosso. How is it possible that the wine is the exact blush of the sunset?

Meanwhile, I leave home tomorrow, launching both my journey and my travel blog. How will my day-to-day world spin without me in it? I will hop off that merry-go-round for a while, trying to see what it is that has gone missing in my own life. Maybe there is nothing missing at all but my own simple attention, and I will find it again.

As Neruda says: “Man has no business with the simplicity or complexity of things.”

Si, certo, Senor Pablo. I guess we’ll see about that.