Reflections on Baltic Tourism and the Helsinki Herring Festival

Click here to view the Scholarworks Article feature.

The Helsinki Herring Festival has been held every fall since 1743 – quite a cultural feat! It’s September, mid-Covid, and while these countries are still open (as opposed to the rest of Scandinavia and much of Europe) This event is happening and my partner Tom and I are not going to miss it. We have two weeks to kill before it begins. We leave Helsinki for a Baltics compare-and-contrast tour of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania with food as my lens. After all, what represents the blending of culture, ecology and economy better than traditional cuisine?

The Baltic countries are up-and-coming. About half the land is forest. Between the flat fields and sea, the land continues to yield healthy food for its people. A Scandinavian child from the Midwest, some of my best memories were hiking in the mountains of Norway with relatives and picking cloudberries, which taste just like they sound. Baltic cuisine has been influenced by New Nordic food styles. Though Finland claims to be Baltic, Norway really can’t. Finnish history and politics, of course, differentiate it, but language similarities and a distance of 60 sea miles make it particularly compatible with Estonia.

In Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, I feel the ancient pulse of trade in these new-to-me Baltic countries. Food begins with breakfast, and hotel breakfasts feature 18-foot spreads — fish and cheese, bread and meat — five kinds apiece, as I remember from Scandinavia, but even more mushrooms and berries. Folks are obsessed with forest and field — foraging. Hotel breakfasts keep with tradition in being sufficiently caloric to build large barns. Business travel is prevalent, but tourism falls away markedly the minute their precious summers are over. By 2026, old Soviet tracks (being a different width) should give way to a new system, Rail Baltica, providing even greater access to central Europe.

Cuisine is a good reason to travel. Forget about potatoes and pork tongue — the stereotypical fare portrayed in popular culture and travel brochures. There are lighter, healthier choices — including vegan. Locavore was a trend here before it was even a word. For example, Tom and I are borscht aficionados, and we compared the borscht at the elegant French-Russian Tchaikovsky’s restaurant in Tallinn with his grandmother’s recipe. Tchaikovsky’s is lighter and prettier, decked out in tiny decorative edible blossoms.

Hospitality everywhere is warm. Despite the famous Baltic reserve and the fact that vaccination cards are demanded everywhere, it is amazing to travel again. Warm welcome takes on a new meaning the day we walk the beautiful white sands of the famous Curonian Spit (the southern half is in Kaliningrad, a Russian enclave). Freezing after a brave dip into the Baltic sea, we jog to a rustic restaurant where they not only serve steaming root vegetable soup, craft beer, and dark earthy rye bread, they also build a fire in the fireplace.

We drive south to Latvia, where the foraging fetish was evident and amusing. In Art Nouveau Riga, I watch Latvian reality TV featuring a family dressed in mushroom costumes searching for mushrooms. Silly Latvians! But that evening, hungry and lost, our waiter in an upscale restaurant named Snob shifts that perspective. Hospitality training like our waiter’s includes schooling in Paris and London, learning both Norwegian and French.

Past the Lithuanian border, we decided to drive to Bialystok, just across into Poland. My last trip to Poland was in 1981 during Solidarity days. Even bread stores then had no bread. People walked the streets holding bright yellow sunflowers and eating the seeds. Now, on a gorgeous fall weekend, families stroll with double rainbow-colored ice cream cones. Ice cream freedom! After the Solidarity movement in Poland, more than a million people all across Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia held hands in unity. By 1990, they were free, with EU membership by 2004.

Having checked the main tourist boxes (the main capitals, the Curonian Spit, and the Trakai Castle to name a few), we head north again along the eastern border of Lithuania near Belarus. There is a near-empty Russian restaurant in Daugavpils, from where Mark Rothko and his namesake art center hails. In a heavy-duty, borscht-less Russian restaurant, we drank the national drink, potent Balsams – as dark and intense as their history. But life is bittersweet; there’s also lovely mead – supposedly the world’s oldest drink made from honey. Beehives appear on the edge of farms and sometimes even fancy hotel roofs. Apple tarts and sweet desserts are close at hand.

On a quiet road, Tom and I brake for a farm stand where three women rise to greet us, bicycles behind them in the long grass. I spy a wealth of figs, chanterelles (my personal obsession), and plump red and yellow apples. Having used Apple Pay and cards for even tiny pop-up stands, we are out of Euros. Sigh. Instead, I snack on gas station candy in the car — pink and blue sugar mushrooms, of course.

We drive to Kaunas, designated by the EU as a “Capital of Culture” for 2022. There’s a functioning synagogue miraculously still standing from pre war days, and we hustle to get there before dark. The two-story brick synagogue is tragic, beautiful, and downtrodden, surrounded by a high fence. It is concrete – proof of man’s inhumanity to man. My spirits and blood sugar are in the gutter, so we stop at the first warm, well-lit place. It turns out to be Tex-Mex. Did I mention we’re from Taos, New Mexico? Baltic enchiladas are not recommended.

On another day, a Lithuanian waitress serves up a two-minute history lesson after we ask her what languages she speaks (Russian and four others). She tells us about her grandmother, who was sent to Siberia. Her grandmother’s greatest wish, she says, was to live to hold her.

“Instead,” she says, “She died four months before I was born.”

I’m immediately in tears. The waitress shouts, “Don’t cry!” (Emotions are hidden here). But I can’t help it. I miss my own baby granddaughter. I order another Aldaris beer and a slice of global comfort food: pizza.

Latvian beer: fabulous; pizza: okay.

The beautiful Holm restaurant in the lively university town of Tartu, Estonia, feels both elegant and earthy. Many of the recipes are the owner’s grandmother’s. My incessant questions are rewarded with several tastings from the chef, including spruce shoots. “Reminds me of Christmas trees,” I say, “or maybe the pine tar we used on the bases of old wood cross-country skis.” Our waiter concurs, making me feel like a gastronomic genius. I think of the Jewish resistance fighters of WWII surviving in these woods on things like mushrooms and spruce shoots. I ponder how the same rations once consumed in despondency now find themselves trending in upscale restaurants…

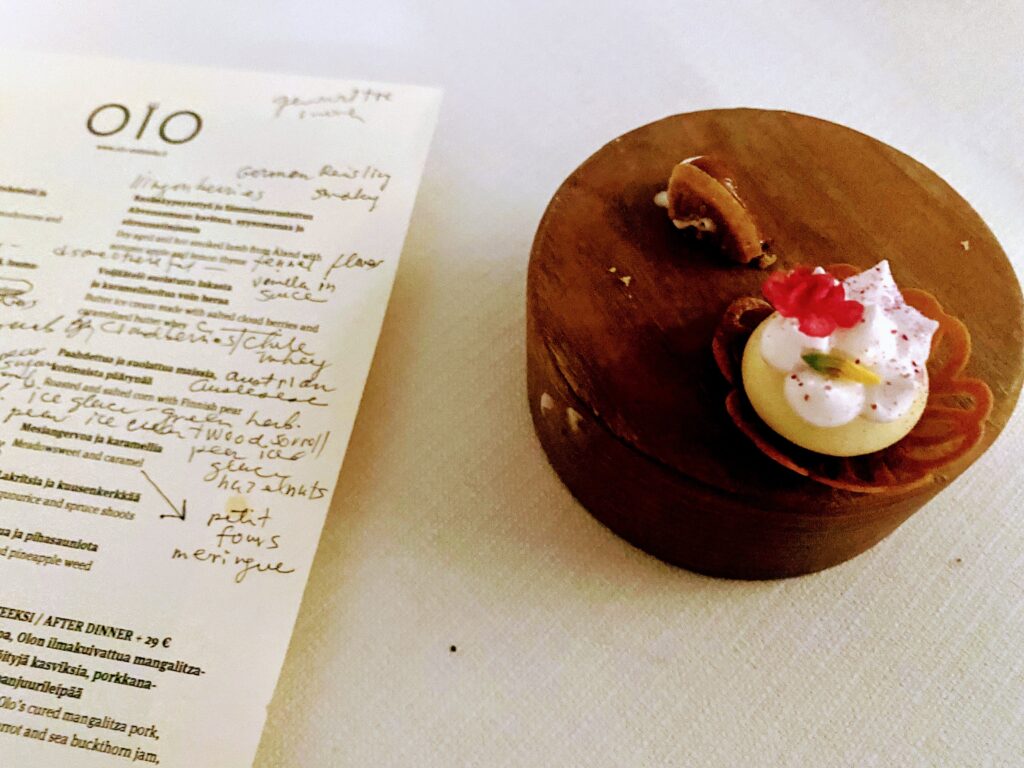

At last, back in Helsinki, we await tomorrow’s opening of the Baltic Herring Fest. First, though, a long-awaited reservation for Michelin-starred Olo, right along the harbor. It is a gastronomic recap of our vacation, a way to savor it all again — an exquisitely choreographed 12-course tasting including sea urchin, quail eggs, tamami salmon, plum vierge, king crab with rhubarb, and whitefish roe. Chefs explain each gorgeous dish. Wines from around the world are surprising yet creatively perfect in their pairings. I take notes. I ask more questions. Tom grows restless. I do not reach for the bill.

What is missing in Olo’s three-hour olfactory and sensory tasting tour of the Baltics? The answer appears the next day at the festival, which functions as an emotional palate cleanser for the man I ignored at dinner last night, sacrificed on the altar of taste — which is, after all, not everything. Here, food is both community and history. Gold leaves float down on this perfect fall Sunday. The blue sea sparkles. At one market stall’s outdoor table, I cherish the grilled salty, silvery, little fishes, staring up at me with crispy tails. I eat them with my fingers. The potatoes are perfect too — small and grilled on a paper plate for 15 Euros, washed down with Diet Coke. This time I pay.

Shouldn’t food offer surprise and delight, but also solidify our relationships not only with each other, but with land and sea and history? I think of white cranes flying over the flat fields, a warm fire and goodwill, riding bicycles through forests with glimpses of the green sea. I was as relaxed as I’d ever been in my life, just wondering what and where the next meal would be. Then at last at the Herring Fest, I rub elbows with my fellow epicureans. I admire the handsome old wooden boats, buy cozy wool mittens and tiny jars of tart lingonberries and heavenly orange cloudberries to share with family and friends. I want to be the first to give a spoonful of cloudberries — the flavor of our heritage — to my tiny granddaughter when I get home.